A Superdrought Emergency, $16 Million in Relief Funds & El Niño

August 20th, 2015

Contributed by Christine St.Pierre

According to NASA, 2014 was the hottest year on record—crops died, land dried, rivers shriveled, and we began feeling the effects of a dry heat that many have never experienced before. But, as I write, I am gazing at a disheartening portion of Mt. Shuksan’s pristine, ice-blue glaciers that have receded into the dark hollows of the mountain’s rocky core, and, next to her, Mt. Kulshan’s (Baker) famed powder looking more like the slushy shoulder of a highway during a Chicago winter—murky from the soil and rock moving beneath the rapidly melting snow—and I wonder what NASA’s records will reveal about 2015’s state of emergency on both the land and sea.

Over the winter, I taught an English lesson on satire to the 2015 graduates of Nooksack Valley High School, located north of Bellingham. The lesson preceded the area’s 93-mile “Ski to Sea” multi-event relay race that traditionally begins with skiing down the slopes of Mt. Kulshan (Baker) and ends with sea-kayaking Bellingham Bay. This year was the first in the 100 year history of the event that was forced to eliminate the ski portion altogether due to an extreme lack of snow. The students resonated with the lesson on satire, creating satirical headlines about the Patriot’s shoddy Superbowl win (“The Deflate-riots”), a search for the new Pope (“The first black, female Pope, Poprah?”), and, with unfortunate poignancy and relevance to the lives of these snowbird seniors, headlines like “Surf Mount Baker!” and “Surf to Sea!” Witnessing these warning signs as early as February frightened me, but I had no idea what terrifying drought conditions would we face in Washington State, on the entire west coast, throughout much of the Midwest, and across the entire globe.

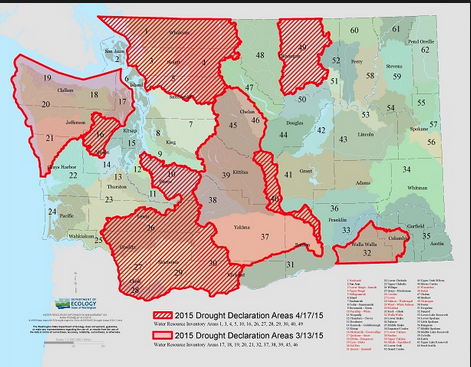

In May of this year, Gov. Jay Inslee declared a statewide drought for Washington for the first time since 2005, following the historic lows of the winter’s snowpack, dwindling river levels that threaten fish populations (not to mention increased temperatures in the shallower river water), and irrigation districts cutting off water to farmers in eastern Washington, an area greatly affected by the rain shadow of the Cascades. Declaring drought for Washington state must meet two criteria: the state must be experiencing or expected to experience a 75 percent reduction in water supply and consumers of this water will experience hardships due to this lack of water.

By May, Washington had already experienced an 82 percent reduction in water supply. The State Dept. of Agriculture predicts a $1.2 billion crop loss this year as a result of the drought, according to the Dept. of Ecology. The Olympic Peninsula is experiencing high-elevation wildfires and the bloom of glacier lilies, where, normally, there is seven feet of snow. “This drought is unlike any we’ve ever experienced,” said Washington Department of Ecology Director Maia Bellon on their website. “Rain amounts have been normal but snow has been scarce. And we’re watching what little snow we have quickly disappear.”

In August, state legislature approved the reallocation of $16 million dollars toward drought relief work, including the support of stream flows for fish, water supplies for farmers, and grant money for cities, counties, and tribes to develop alternate water sources and purchase or lease water rights for the 2015–17 biennium. This approval arrived just in time to address the seriously scary possibility that this year’s El Niño could be the most extreme in history, making for a difficult recovery over the next few years.

El Niño, associated with dry winter and spring conditions, is upon us. In order for this rare and complex climate event to take place, three things must occur simultaneously: eastern trade winds weaken, sea temperatures rise, and the southern oscillation index must be -7 or below (which it has been since 2014). To spare you a layman’s description of what scientists expect to be a “Godzilla” El Niño, I’ll sum it up briefly: trade winds across the Pacific Ocean weaken, releasing a pocket of warm water near Indonesia that travels eastward, then sinks along with the thermocline, which means less cold water is rising up from the deep ocean near South America, reducing rain much of southern hemisphere. For we on the west coast, rain tends to follow the warm pool of water—although, this year, scientists aren’t too sure it can end the drought. In addition, heavy rains after a drought can bring upon heavier mudslides and floods.

It’s a lot to accept all at once — Central California looks like the post-apocalyptic set of Mad Max, Oregon’s on fire, and Washington’s land and rivers are shriveling in the heat. We’ll see what the weather brings to us throughout the rest of the year, but we can’t regrow glaciers in our lifetime or turn back the clock. Things — “they are a changing.”

Leave a Reply